We end our visit with hugs and kisses.

She says this is the first time she has spoken so honestly about her life,

and it feels liberating. Dinner with Dimitri3

At the age of 14 Dimitri told his parents he was a girl. They reacted by admitting him to an institution and when out, secretly medicating him through the food his mother prepared for him. He fled to Athens and was homeless for years, returning to his tiny village to take care of his sick mother— for 25 years. Once she passed away, Dimitri started wearing women’s pants and shirts and only in 2014 did he put on a dress and walk around outdoors in his tiny home village of Skala Sikaminias on the island of Lesvos.

We thank Rory Aurora Richards for sharing her experience.

I was starting to worry it wouldn’t happen. Not only was I running out of time, it was my last day in the 300 person Greek fishing village of Skala Sikaminias.

I had an idea in my head, and a very strong instinct to capture a local, named Dimitri, on camera. However I couldn’t do it alone, and I was finding it impossible to find anyone with a camera that would take my interest in Dimitri seriously.

‘He’ is known by locals as the crazy village cross dresser in the tiny town I was staying in on the Island of Lesvos. I saw her every day, strolling around the village alone, peacefully. Seemingly unfettered by the snickers and eye rolls that would erupt her wake.

Then I met a Swedish man named Torbjörn Stenberg. We met by chance at breakfast in the village and I mentioned my interest in learning Dimitri’s story, and capturing a sliver of it on film to possibly entice a filmmaker to see Dimitri as a subject of a documentary.

‘I know exactly who you are talking about.’ said Torbjörn, ‘ I think it is wonderful. I’m not a professional, but I have a camera. Let’s do it!’

Finally, someone who didn’t think I was crazy!

Now before I start to tell Dimitri’s story, or at least a part of it, I need to put one matter on the table, and that is the issue of which pronoun to use. I asked Dimtri about identifying as male or female, and, not that it was a surprise, the answer was female. So I will refer to Dimitri as ‘she’ from now on. This story is told with consent and blessing.

…

We arrived at Dimitri’s house on Christmas eve.

She greeted us in a hot pink cocktail dress, pearls and a smile that was worthy of crowning a Christmas tree.

She was beaming.

Her house is a modest village abode. The floors and walls are concrete, and the smell of moisture tinged the drafty air inside. There is no indoor washroom, only a wash closet outside on the porch with a simple tap and toilet.

The furnishings are likely the original pieces Dimitri grew up with as a child. It is the house she was raised in with her parents and siblings. Although the environment reveals it’s age, it is clean and tidy, and the weathered walls of every room are covered with colourful religious imagery and family photos that have been placed with thoughtful symmetry and care.

We have brought wine and pizza from the taverna and settle in at the dining room table to talk. Dimitri tells us that this is the first time anyone has come over to visit her.

Really?

Yes, really.

Christmas music plays in the background and festive decorations are displayed throughout her home. I am touched by the enthusiasm in her solitary world. I enjoy a bouquet flowers on the table, but as a person who also lives alone, I generally hesitate to buy them unless I have guests coming. I appreciate the effort Dimitri has made to create a warm and personally expressive environment for herself. It shows presence and self care, and I admire it.

She is delighted, excited and a bit overwhelmed to finally have guests in her home. She offers us homemade liquor several times but keeps forgetting to bring the glasses to the table. There is so much she wants to show and share with us that it is hard to focus on just one thing.

Fortunately we have 2 young waitresses from the taverna serving as our translators and they manage to make sure we have a glass and a toast as we begin our visit.

Dimitri describes growing up in the small fishing village with her siblings and parents. She describes her mother as a deeply religious and devout woman and a source of true and unconditional love for Dimitri. She describes her father as angry and transient. A father who would go in and out of the family unit, disappearing for periods of time, and the house being a war zone whenever he returned home. But somehow it was still a family, and Dimitri’s parents remained married to each other until they both died 7 years ago. They died within 6 months of each other.

Dimitri said she had a clear feeling from a young age that she was different. When she was 14, she told her parents that she was a girl. An admission that she was consequently removed from the home for, and sent to a mental institution by her devastated and confused parents.

When she was finally allowed to return home, the doctors insisted to her parents that she should remain medicated, possibly for the rest of her life. Dimitri did not want this. She hated the way the medications made her feel. Her parents resorted to drugging her by hiding the medication in her food.

However Dimitri’s sense of self was not something that medication could dissolve, and throughout her teenage years she continued to insist that she was a girl to those that asked. Her natural honesty ostracized her in the village, bringing gossip and shame to her family and more stress to her parent’s already strained marriage.

She certainly did not experience any adolescent romances. Just a series of tragic, secret crushes on boys. There was little chance she would find a boy in the village that would return her feelings. She was an outcast.

She speaks candidly about struggling with suicidal thoughts her entire life, making several attempts at different stages of her life, starting as a teenager.

In her words, the closest anyone ever came to showing interest in her was when she was a teenager swimming nude alone in the ocean. An older man from the village appeared and told Dimitri he wanted to rape her. Dimitri was terrified. This man secretly stalked and harassed her for many of her teenage years.

However looking back, Dimitri has no bitter feelings towards this man, in fact she has compassion. She thinks the man has a dark soul as a result of never having been loved. Dimitri had the security of her mother’s love, which saved her.

Eventually at the age of 20, Dimitri left the village and the Island of Lesvos, and ran away to the big city, living on the streets of Athens for almost 5 years. There she occasionally worked odd jobs in supermarkets, but even in the big city people sensed she was different and again she was sidelined from society. As a result, even in the population of Athens, Dimitri never found love or companionship, except for one woman friend, who was also homeless. They shared a pretend fantasy they were married and would one day have a child.

To have a family of her own is a dream that she has had her entire life.

A dream she believes will make her life complete.

A dream that holds the ‘forever love’ that she has always been missing in her life.

Eventually she was forced to leave Athens when her mother became ill. Dimitri’s older siblings had long since left the village and the dysfunction of their home. There was no one else to care for her mother. Dimitri’s father was too unreliable to be considered a suitable caregiver.

Dimitri lived with and took care of her mother for the next 25 years. Her death was devastating and marked the loss of the only source of companionship and love in her life. She was truly alone in the world now.

The pull of suicide was stronger than it had ever been before. It was then Dimitri decided to do something she had never done before.

She started to wear women’s pants and blouses.

With this shift in external expression came a deep sense of relief and comfort.

Dimitri started to feel better than she had in her entire life.

She felt herself becoming whole for the first time.

I asked Dimitri how the people in the village responded.

Dimitri said they responded naturally, considering they see her as a man wearing women’s clothing. But it wasn’t exactly a surprise to the people in the 300 person village she grew up in, but yes of course, there was a reaction.

She harbors no hard feelings to anyone, because, according to Dimitri, the only thing that matters is being honest. After spending her entire life as an outcast, and her mother now gone, she doesn’t really have anything to lose, except herself. She feels shielded by the authenticity of being her true self, and that, to her, is all that matters now.

Last summer she started wearing dresses.

When I asked her if she feels the need to physically transition to a female, she says no. That she may have wanted to when she was younger, but not anymore. She says that she finally feels natural in her body just as she is. That whether she is wearing clothes or completely naked, she finally feels at one.

At the same time she realizes she is alone, with no friends or companionship, or even anyone to talk to. Dimitri says that the only people that talk to her are the children of the village.

However, despite the social isolation, Dimitri insists that she is happier than she has ever been in her life. She is inspired by music and fashion, spending what little money she has on new dresses or vintage albums. She is a huge fan of the Greek opera legend, Maria Callas…and loves classic screen sirens like Greta Garbo.

Photo by Kelly Melton

Does she ever want to leave the tiny fishing village of Skala Skamania?

No. She is content to live in the house she shared with her beloved mother.

I ask her what she would say to a younger Dimitri…

‘To keep your heart young. To remain pure inside.’

I told her that I have written about her and posted photos, and that many people have been inspired by her.

She blushes with modest delight.

Then I pull out our Christmas present.

She is overwhelmed.

I think it has been a while since she has received one.

Especially one like this.

Inside is her first purse, and a sleek black dress and belt.

And even though ‘black is not her colour’, she loves it.

‘We don’t have fashion, we have style.’ she says, quoting Coco Chanel.

I ask if she had a wish, what would be?

She said she just wants everyone to have peace and respect for each other. That both man and woman embrace each other as one, and come to understand each other.

Dimitri says she has compassion for the refugees because the refugees are escaping something horrible.

They are leaving everything behind and have nothing, and she knows what that feels like.

We end our visit with hugs and kisses.

She says this is the first time she has spoken so honestly about her life, and it feels liberating.

Outside Dimiri’s house I thank the young taverna girls for taking the time to translate, and commend them on their maturity and presence to hold space and serve as Dimitri’s voice for our visit.

I ask them how that was like for them.

‘I am very surprised. I …of course know, and heard stories about Dimitri…that he is crazy, and on medications since he was very young…but now that I speak with him, I don’t know why he would be on medication. He is normal. I mean, he is different, obviously, but he is not crazy.’

‘I never knew anything about him personally. Just the way he look. I did not know his story. Or her story. She has had such a hard life, but is so positive about everybody.’

‘ I live across the street from Dimitri for many years. Just a few meters from here. I see him in the village and coming in and out of his house. And hear the music that he always plays. But I just never knew all the things that I learned tonight. I don’t know how to say it, but it change for me inside.’

‘I see his face now, and it is natural. It is calm. I did not see him this way before, so natural. He is special person. I did not know he was so alone. I feel very bad. I feel comfortable now to stop and talk, to maybe come here again and take a tea. ’

___

Back at the taverna Torbjörn and I solemnly digest all of what we have heard.

Dimitri has clearly had a very tough life because of her gender.

Neither of us can comprehend her journey, and her isolation.

But we both marvel about her gentleness and poise.

However at times she spoke in religious metaphors that were hard to understand, and could be translated as being a little crazy. But like the taverna girls, we agree that Dimitri is not crazy. But she has spent a lot of time in her own head, and also immersed in religious ideology, which is a strong link to her mother. It is natural that she would search a religious context for some way to explain or find herself. At several points she said that she feels pregnant, and that she is both a man and a woman.

Torbjörn and I both reflect on this point in the conversation with each other and whether she actually believed that, or if she was speaking metaphorically… and if what she was really trying to articulate is that she is ‘twin spirited’.

Torbjörn and I both say the words ‘twin spirited’ at the exact same time.

(I just got goose bumps as I was typing this.)

We are also connecting the dots with things we know to be realities for other trans people like Dimitri…isolation, homelessness, suicide…common markers in the lives of so many trans people that have been marginalized or cast off by a society that did not understand, value or accept them.

Somehow, Dimitri has survived it all. With grace and kindness still in her heart.

Torbjörn and I both wished the language was not such a barrier and that we had more time with her. We both agree that Dimitri’s story is a story that begs to be told, perhaps by an LGBTQ Greek filmmaker. Her story, contrasted by nuances of the village, Greek culture and history, can only be truly captured by a Greek.

If you are reading this and you feel the same, help us reach members of the Queer community in Athens. Let them know Dimitri is in the village, and ask them to reach out to her. May branches of community and friendship be extended to her from all of us .

Thank you, Dimitri.

Thank you for being you,

Thank you for keeping the pilot light of your true self lit for all these years.

The world is a much brighter place because of it.

Long may you reign.

#onelove

Photo Credit: Torbjörn Stenberg

Translation by the taverna girls: Liza Nanasou and Mary Hara

http://www.pappaspost.com/dinner-with-dimitri/ |

Πέμπτη 31 Δεκεμβρίου 2015

Η ιστορία της Δημήτρη από τη Σκάλα Συκαμνιάς / DINNER WITH DIMITRI

We end our visit with hugs and kisses.

She says this is the first time she has spoken so honestly about her life,

and it feels liberating. |

Τετάρτη 30 Δεκεμβρίου 2015

‘Famiglie in-attesa': tutto ciò che non sai sull’omogenitorialità

Eugenia Romanelli

Scrittrice, giornalista e docente

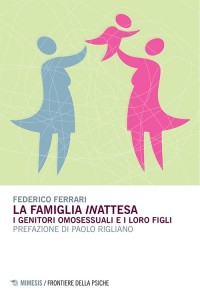

Qualche giorno fa è uscito un libro molto interessante e decisamente utile per chi non ha ancora un’opinione in merito all’omogenitorialità, ossia a quelle famiglie composte da due genitori dello stesso sesso. Si intitola “La famiglia in-attesa” (edizioni Mimesis) ed è a firma dello psicologo e psicoterapeuta Federico Ferrari, didatta del Centro Milanese di Terapia della Famiglia.

A pensarci bene, in realtà, il libro è utile a tutti, visto che la letteratura scientifica internazionale sull’argomento è molto giovane (appena trent’anni) e che in Italia esistono solo un paio di studi, e che quindi non esistono emeriti in materia. E’ utile agli addetti ai lavori (ricercatori, operatori sanitari e del diritto, psicologi, psicoterapeuti, etc) ma anche a tutti gli altri cittadini, perché informa in modo laico e non ideologico su una specificità della contemporaneità tanto complessa quanto delicata, su cui militanze opposte hanno contribuito a creare un disorientamento pericoloso per il destino di tanti bambini e bambine che ad oggi non sono tutelati dal diritto italiano.

I 5 capitoli guidano in modo approfondito all’esplorazione degli studi scientificamente rilevanti pubblicati nei vari continenti con l’obiettivo di separare e distinguere opinioni personali e pregiudizi dai dati oggettivi, e ambientare quindi il dibattito nel campo neutro della conoscenza. La costellazione tematica che rubrica il volume è molto varia e offre una panoramica veramente dettagliata, rispondendo alle domande e alle curiosità più microscopiche. Si va dalla descrizione dell’attualità politica al racconto dei differenti percorsi necessari per diventare omo-genitori, sia nel caso delle due mamme che in quello dei due papà; si spiegano le varie tecniche (surrogacy, inseminazione artificiale, etc), si identificano le problematiche (identità sociale, riconoscimento istituzionale, ruoli di genere, identità sessuale dei figli, omofobia, stigma sociale, etc), e si discutono i paradigmi culturali e simbolici legati al genere, all’eterosessismo e al pregiudizio.

Credo che un libro del genere andrebbe letto da chiunque sia coinvolto (o si senta tale) nell’esercizio di una funzione pubblica, dagli opinion leader agli insegnanti, dai politici ai legislatori, dagli intellettuali ai medici, dai giornalisti ai comici, fino agli artisti e aglishow-man. Perché insegna a pensare qualcosa che non si sa pensare, qualcosa che non riusciamo a figurarci perché non è mai esistito finora né si conosce, e in questo modo aiuta a trovare le parole per dirlo, comunicarlo, sceneggiarlo, trattarlo, comprenderlo, raccontarlo, e così via, formando l’immaginario che manca, costruendo un dialogo libero, aperto, creativo.

Ma “La famiglia in-attesa” non fa luce solo sulle nuove forme dell’amore genitoriale: si spinge ad indagarle con scrupolo e lungimiranza fino ad integrare, come spiega nella prefazione il bravoPaolo Rigliano, il punto di vista dei “nuovi” genitori con quello dei “nuovi” figli, e a individuare il processo di costruzione del sé-figlio in rapporto al sé-genitori. “Questo testo – sostiene Rigliano – si distingue per originalità e rigore, perché a differenza di altre pubblicazioni finora apparse nella letteratura internazionale, dischiude la profondità complessa del fenomeno, illuminandone tutti gli aspetti problematici, le domande destabilizzanti, i punti poco chiari, le questioni oscure alla gran parte dei lettori, avendo il coraggio di farsi carico delle inquietudini, delle paure, delle incertezze di tutti”.

E soprattutto, aggiungo io, al libro va il merito di riflettere in modo raffinato ma concreto su questioni antropologiche fondamentali che uniscono invece che dividere, perchè riguardano tutti: cosa fa di un genitore un buon genitore? Cosa significa far crescere i figli nella salute e nella verità? Perchè è indubbio che se l’amore omosessuale ci ha costretti a interrogarci sul significato dell’amore, la genitorialità omosessuale ci costringe a interrogarci sul significato della famiglia. Lo dice bene Rigliano, “la storia dell’umanità può anche essere vista come lotta per il superamento di qualche Ordine che si pretende assoluto e che viene imposto come naturale e sacro”, quella che hanno combattuto tutte le comunità discriminate, dalle donne ai neri, dagli ebrei agli eretici, e tutti i portatori di qualche differenza, coloro cioè che si sono impegnati nella scomposizione e ricomposizione di Weltanschauung (?) troppo rigide ed esclusive per conquistare nuove forme di valorizzazione della vita.

Insomma, a Ferrari il merito di fornire a tutti uno strumento oggi divenuto urgente per orientarsi in un dibattito confuso che spacca la società, chiamata all’impossibile scelta se aderire alla militanza Lgbtqi o al fondamentalismo dei gruppi cattolici reazionari. Di sicuro, dopo questa lettura, nessuno rischierà più di farsi manipolare da fantasiose campagne “antigender” né da qualunque altra istigazione all’odio contro le famiglie arcobaleno, perché l’esercizio etico del confronto sui valori comuni diventa punto di non ritorno nel cammino verso l’emancipazione personale e culturale e verso la valorizzazione di una umanità plurale e unita. Chapeau.

Τρίτη 29 Δεκεμβρίου 2015

Γράμμα στα αγέννητα παιδιά μου, από την λεσβία μητέρα τους

Μια 19χρονη που πέρα και πάνω από όσα πιστεύουν οι άλλοι γύρω της μπορεί επιτέλους να ονειρευτεί την οικογένειά της και τα παιδιά της και ξέρει ότι αυτό το όνειρο θα το κάνει πραγματικότητα.Για μας είναι μεγάλη χαρά καθώς νιώθουμε ότι ανοίξαμε ένα δρόμο. Στα πρώτα κείμενα της ομάδας οι λέξεις λεσβία + μητέρα ήταν σαν να μην μπορούν να είναι μαζί, σαν να δημιουργούσαν σχήμα οξύμωρο, σαν να αναιρούσαν η μια την άλλη. Σήμερα με το παράδειγμα των οικογενειών μας έχει αρχίσει να σπάει το ασυμβίβαστο των όρων. Αύριο με όλες τις οικογένειες που θα δημιουργήσουν τα σημερινά 19χρονα αγόρια και κορίτσια θα γίνει εντελώς κομμάτια και θρύψαλα, θα γίνει σκόνη και θα σκορπίσει πάνω στους μπουφέδες και τα σύνθετα των γιαγιάδων και των παππούδων που θα καμαρώνουν τα εγγόνια τους και θα θεωρούν αυτονόητο ότι η λεσβία κόρη τους ή ο gay γιος τους έκανε οικογένεια και παιδιά.

http://www.lifo.gr/lifoland/you-send-it/84934

Γράφει η αναγνώστρια της Lifoland, M.

26.12.2015 | 20:29

Μελλοντικά

παιδιά μου, είναι ξημερώματα Τετάρτης 24 Δεκεμβρίου 2015. Σήμερα ψηφίστηκε

το σύμφωνο συμβίωσης για τα ομόφυλα ζευγάρια στην Ελλάδα, για τα ζευγάρια σαν

εμένα και τη μαμά. Ή μπορεί να ψηφίστηκε κι εχθές αλλά είναι ξημερώματα κι εγώ

τώρα μπήκα σπίτι. Δεν μπορώ ακριβώς να περιγράψω το πως νιώθω. Δεν ξέρω

πώς να περιγράψω αυτή τη χαρά που μετά από λίγες σκέψεις μετατρέπεται σε πικρή

χαρμολύπη.. Βλέπετε σήμερα για πρώτη φορά ένιωσα πως υπάρχω για αυτή την

κοινωνία.

Υπάρχω σαν λεσβία γυναίκα, υπάρχω σαν γυναίκα που ερωτεύεται γυναίκες

και μεγαλώνει παιδιά με μία γυναίκα και τα αγαπάνε και τα φροντίζουν και

ξεριζώνουν μαζί τις καρδιές τους και τις αφήνουν στα χέρια τους κάθε

μέρα. Που λέτε σήμερα κατέβηκα στο Σύνταγμα στις 7 το απόγευμα

μαζί με τη θεία Κ. και άλλους φίλους. Σταθήκαμε εκεί, περιτριγυρισμένοι από

άλλους πολύχρωμους ανθρώπους και περιμέναμε έξω από τη Βουλή, σαν τους

συγγενείς που περιμένουν έξω από την αίθουσα του μαιευτηρίου. Μόνο που το μωρό

που περιμέναμε εμείς ήταν η αξιοπρέπεια μας, η ελπίδα ότι μας επιτρέπεται να

διεκδικήσουμε κι εμείς ένα κομμάτι ευτυχίας από τη μεγάλη πίτα της ζωής.

Περιμέναμε ένα νεύμα – όμορφο και χαμογελαστό από αυτούς που έχουμε εκλέξει

υπεύθυνους για τις ζωές ότι μας υπολογίζουν, ότι μας θεωρούν μέλη της κοινωνίας

τους, ότι μας αναγνωρίζουν ως άτομα άξια δικαιωμάτων και υποχρεώσεων και όχι ως

πρωταγωνιστές σε σεξουαλικές φαντασιώσεις και θλιβερά ανέκδοτα.

Και

πράγματι 195 από αυτούς μας έγνεψαν. Ήταν ένα νεύμα λειψό και καθόλου επαρκές

για να μπορώ να λέω ότι η οικογένειά μας είναι ίση με την οικογένεια του

διπλανού διαμερίσματος. Για να μπορώ να μοιραστώ την επιμέλεια σας και τη

γονεϊκότητα με τη μαμάς σας με ό,τι αυτό νομικά και πρακτικά συνεπαγεται. Δεν

ήταν χαμογελαστό. Αλλά δεν πειράζει – για απόψε. Απόψε χαμογελάσαμε εμείς κι

αυτό μας φτάνει – για απόψε. Όταν πήραμε τα νέα είχαμε φύγει από το Σύνταγμα

– δεν αντέξαμε το κρύο και την αναμονή και λιποταχτήσαμε. Τα νέα τα μάθαμε μέσα

σε ένα κλαμπ - από το πορτιέρη! Τον ρώτησε η θεία Κ., ήρθε μέσα και μου το

είπε. Μου το είπε και αγκαλιαστήκαμε. Κι εκεί μέσα στη μουσική του κλαμπ σαν να

δάκρυσα και η πρώτη μου σκέψη ήσασταν εσείς. Κι ας μη σας ξέρω ακόμα. Κι ας μην

υπάρξετε ποτέ. Κι ας πεθάνω μαγκούφισα με 24 γάτες. Εγώ θα θυμάμαι για πάντα

αυτή την νύχτα. Και το τι ένιωσα.

Και από αύριο σας το υπόσχομαι,

θα συνεχίσω να παλεύω. Κι ας διαβάζω κι ας ακούω κάθε, μα κάθε μέρα έναν οχετό

μίσους για άτομα σαν εμάς. Εγώ και πολλοί άλλοι θα συνεχίσουμε να παλεύουμε.

Ξέρετε για τι? Για τα πρωινά που θα δίνουμε μάχη με την μαμά σας να σας

ξυπνήσουμε για να πάτε σχολείο. Για τις παραστάσεις σας που θα βιντεοσκοπούμε

και θα αρχειοθετούμε σα χαζομαμάδες. Για τις φορές που θα σας πάμε έντρομες στο

γιατρό κι εκείνος θα μας πει πως είναι περαστικό και θα μπορέσουμε να

ξαναπάρουμε ανάσα. Για εκείνη τη στιγμή που θα στεκόμαστε με τη μαμά πάνω από

το κρεβάτι σας και θα σας φιλήσουμε για καληνύχτα και θα χαμογελάσουμε με μια

απέραντη ευγνωμοσύνη που βρήκαμε η μία την άλλη για συνοδοιπόρο σε αυτή τη ζωή

και που έχουμε εσάς να σας την αφιερώσουμε.

Εύχομαι αυτή να είναι η

πρώτη νίκη αυτού του δύσκολου αγώνα. Εύχομαι μέχρι να γεννηθείτε να έχει

αλλάξει ο κόσμος ή κι ο κόσμος να μην έχει έρθει ανάποδα να έχουν αλλάξει

πλήρως αυτοί οι σκασμένοι, οι στριφνοί οι νόμοι που τώρα αρχίζουν να μαθαίνουν

ότι υπάρχει αγάπη σε αυτή τη χώρα που πρέπει να την διευκολύνουν για να ανθίσει

και να δώσει στο δέντρο της κοινωνίας ευτυχισμένους πολίτες που ξέρουν να

αγαπιούνται και να αγαπούν. Εγώ και η μαμά σας, είτε παντρεμένες είτε

«συμφωνημένες», θα σας προστατεύουμε και θα σας αγαπάμε πάντα. Σας το

υπόσχομαι. Η 19χρονή –ελπίζω- μέλλουσα μαμά σας. Πηγή:www.lifo.gr

Εγγραφή σε:

Αναρτήσεις

(

Atom

)

Powered by EMF Web Forms Builder

EMF Web Forms Builder

Report Abuse

EMF Web Forms Builder

EMF Web Forms Builder